Amalia Kozloff is the Senior Curator at MoPOP.

Here's What Tattoos Have to do With 'The Illustrated Man'

Ray Bradbury’s use of the Illustrated Man is a literary device common throughout history. From Shahrazad in One Thousand and One Nights to Crypt Keeper in Tales from the Crypt, authors have used a mysterious storyteller to set the stage for loosely connected short stories. Many of the stories selected for The Illustrated Man had been previously published and needed such a device to link them into a single compendium.

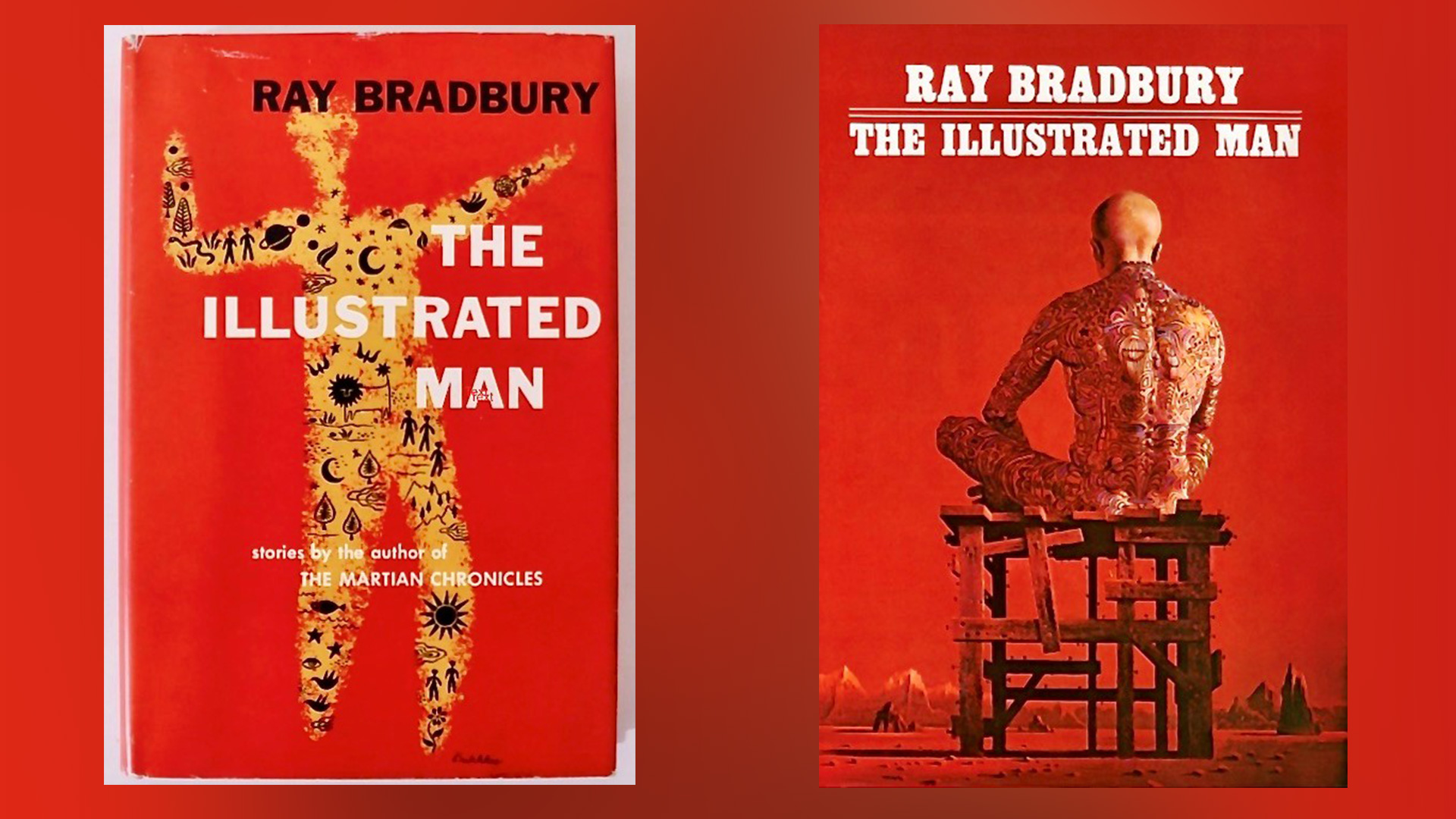

However, Bradbury’s use of tattoos as literary device was a new and unique twist in this storytelling tradition. Not only was it an original premise for the time but having a fully tattooed person on the book cover would have been titillating for many Americans. While the cover of the first edition only hints at nudity and tattoos, by the second edition, the art more closely resembled popular pulp fiction illustrations of the time—a format where many of these stories had been previously published—and featured the back of a seated, nude, fully tattooed man. This imagery would have further sensationalized the newly popular genre of speculative fiction where interplanetary colonization, alternative earths, automated homes, and AR would have been groundbreaking concepts to a 1950s audience.

- Learn More: MoPOP Book Club

The use of tattoos also serves to underscore the pervading sense of human disconnection recurrent throughout the stories. It is not until the last story that the narrator’s own experience becomes entangled in that of the Illustrated Man and his tattoos.

This literary device also serves to drive several other recurrent story concepts that share a commonality with tattoo culture and its history: tattoos and tattoo artists as vehicles for mysticism and mystical forces, common in other cultures but not in mainstream American consciousness; the ready appropriation of other cultures into mainstream popular culture; the sense of self-awareness of how perceptions of different cultures and people can create a certain tolerance for the act of colonization; and how misconceptions are frequently used to excuse the “othering” of those that may appear different from oneself.

Much like the narrator’s reaction to the Illustrated Man:

“What seems to be the trouble?” I asked.

For answer, he unbuttoned his tight collar, slowly. With his eyes shut, he put a slow hand to the task of unbuttoning his shirt all the way down. He slipped his fingers in to feel his chest. “Funny, he said, eyes still shut. “You can’t feel them but they’re there. I always hope that someday I’ll look and they'll be gone. I walk in the sun for hours on the hottest days, baking, and hope that my sweat’ll wash them off, the sun’ll cook them off, but at sundown they’re still there.” He turned his head slightly toward me and exposed his chest. “Are they still there now?”

After a long while I exhaled. “Yes,” I said. “They’re still there.”

The Illustrations.

And, all concepts that still permeate American culture and tattoo culture today.

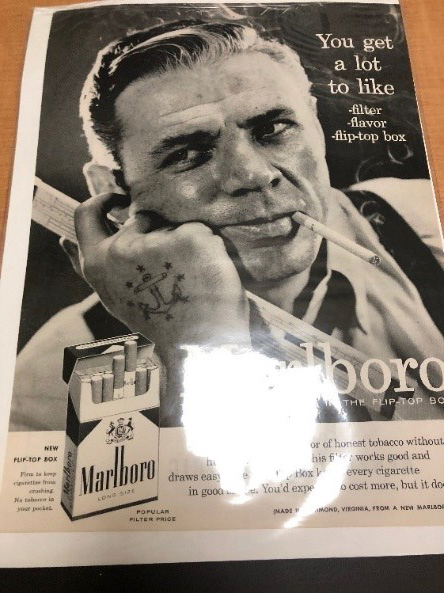

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, tattooing was banned in many American cities. At the time Bradbury published The Illustrated Man, most Americans still saw tattoos as the purview of sailors, criminals, and carnival sideshows. Yet, with Norman Rockwell’s “The Tattoo Artist” gracing the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1944 and men returning home from World War II bearing the tattoos they had gotten during their service, tattoo culture was quietly becoming more accepted. The emerging 1950s counter-cultures, including Greasers and Hep Cats, also actively embraced tattoo culture and proudly showcased their artwork framed by their iconic, rolled-up shirt sleeves. Commercial advertisements of the time began to reflect the fashions of these new, popular counter-cultures, presenting an alternative masculine ideal (and that is an entirely different rabbit hole!) including applying fake tattoos to the Marlboro Man. Even Bradbury’s description of the Illustrated Man with his muscular, oversized physicality reflects this new ideal of decorated masculinity.

(From 'Body of Work: Tattoo Culture' MoPOP Exhibit, 2020)

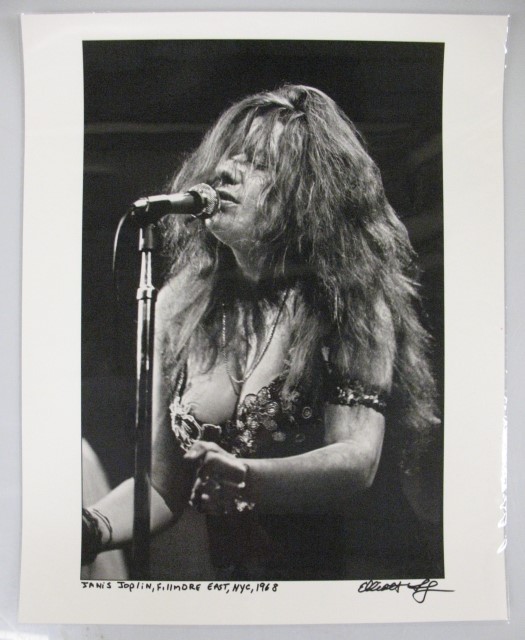

The 1960s ushered in an era of dramatic social change in the United States. Identity politics became a way for young people to express themselves. This took on many forms, including hippie fashion and expanded interest in tattoo culture. Widespread media coverage of new social movements brought greater visibility to women, LGBTIQA+ communities, and communities of color (BIPOC) who bore their tattoos proudly. In the late 1960s, tattoo artists found a new measure of fame and became associated with some of the period’s most iconic stars. Janis Joplin was the first, modern celebrity to embrace tattooing, propelling the artform into mainstream consciousness through her massive popularity with the display of several tattoos by Lyle Tuttle, who was featured on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1970.

In the 1980s and ’90s, tattoos became even more mainstream. On MTV, people saw their favorite musicians’ tattoos up close, broadcast into every home across America. As the Riot Grrrl movement and second wave feminism gained popularity, more women were getting tattooed than ever before.

(Elliott Landy - "Janis Joplin, Filmore East, 1968" digital print. MoPOP Permanent Collection.)

By the 2000s, tattoo was firmly established as a respectable artform, no longer on the fringes of society. Tattoo reality shows, celebrities with visible ink, changes to the industry itself, such as increased safety practices, and the popularity of tattoo-inspired clothing, gave rise to an entirely new celebrity tattoo culture.

Tattoo is not only mainstream, it’s everywhere. More recently, social media platforms have been instrumental in giving artists and collectors a visual platform to reach new global audiences. And popular culture itself is now the inspiration and subject of many contemporary tattoos. As real-life tattoos have become more popular, more pop culture has mirrored that trend, using tattoos to drive narratives and character development in new and unique ways—much like Bradbury was doing back in 1951.

(From 'Body of Work: Tattoo Culture' MoPOP Exhibit, 2020)

Learn more about MoPOP's Book Club + 'Body of Work: Tattoo Culture' exhibition, plus for contests, the latest news, and behind-the-scenes content, be sure to follow us on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Like what you see? Support the work of our nonprofit museum by making a donation to MoPOP today!